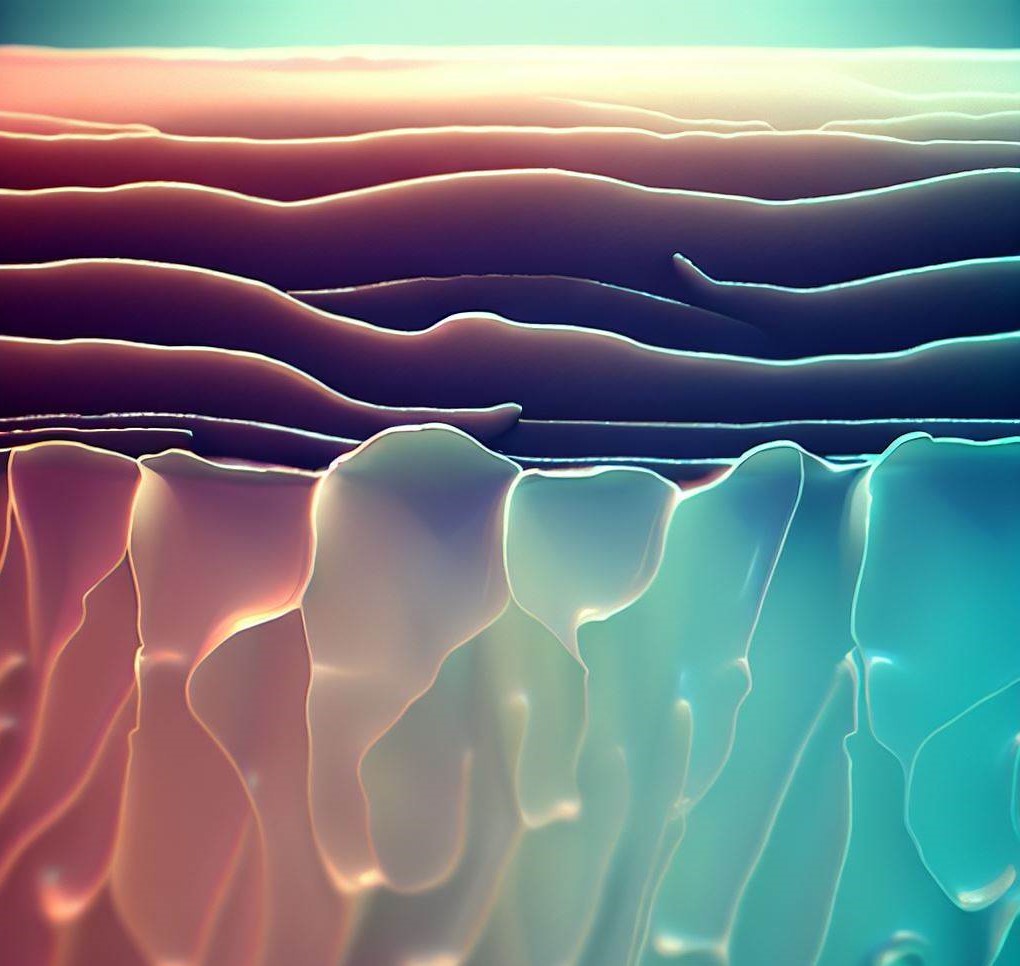

During the first charge and discharge of a Li-ion battery, the electrode material reacts with electrolyte at the solid-liquid interface. After the reaction a thin film is formed on the surface, where Li ion is embedded. It is called solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) and its typical thickness is 100-120 nm, and they are composed of carbonate, fluoronate, oxide, etc.

The SEI acts as a protective layer that prevents direct contact between the electrode and the electrolyte, reducing the risk of further electrolyte decomposition. It stabilizes the interface between the anode and the electrolyte, thus contributing to the battery’s overall stability. The SEI enables the smooth transport of lithium ions between the anode and the electrolyte, enhancing the battery’s efficiency and performance. Also the SEI contributes to the battery’s capacity retention (the ability of a battery to maintain its original capacity) over multiple charge-discharge cycles. However, as the thickness of the SEI increases to the point where electrons cannot penetrate it, a passivation layer is formed, preventing the continuation of the redox reaction.

The SEI remains an active area of research in the field of Li-ion batteries. While the formation of SEI is essential for battery operation, it also poses challenges that impact battery performance and longevity. In some cases, the SEI can become unstable and lead to dendrite growth on the anode’s surface. Dendrites are lithium metal structures that can penetrate the separator and cause internal short circuits, posing a safety risk. The SEI is formed through the decomposition of the electrolyte at the anode-electrolyte interface. Understanding and controlling this process is crucial for improving battery performance and stability. In this week’s nature journal, (1) there was a report on the SEI formation mechanism at ultrafast current densities under various different electrolyte conditions. They prepared the four different common morphologies of Li metals. (filaments, nanorod, columns or chunks) Surprisingly, although the initial stage of the molphologies was different, all the structure had a transition to a well-defined faceted polyhedron. Cryogenic electron microscopy identified this morphology as a rhombic dodecahedron, which persists regardless of electrolyte chemistry or current collector substrate, indicating that it is independent of SEI influence. Four model electrolytes with diverse chemistry were chosen to deposit metallic Li at normal and ultrafast rates, resulting in varying SEI layers, Li deposition morphologies, and Coulombic efficiency. At an ultrafast current density of 1,000 mA cm−2, a morphological transition to well-defined faceted Li polyhedra was observed in all electrolytes. At ultrafast current densities, the morphology of Li metal deposition becomes independent of electrolyte chemistry, indicating that Li deposition and solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation can be decoupled. Li electrodeposition and SEI formation likely proceed in a stepwise manner, with Li deposition occurring first electrochemically and SEI formation proceeding chemically after Li deposition. At ultrafast current densities, Li+ transport to the Li surface is similar to bulk liquid diffusion, while at normal current densities, Li+ transport is slowed by three orders of magnitude due to the SEI layer. This research indicates, by outpacing SEI formation and decoupling it from Li metal growth, they can open up new opportunities to explore how reactive metal deposition fundamentally.

(1) Yuan, X., Liu, B., Mecklenburg, M. et al. Ultrafast deposition of faceted lithium polyhedra by outpacing SEI formation. Nature 620, 86–91 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06235-w

Leave a comment